The Good Owners

Guide to Dogs (beta)

Start Here

Read First: What is the Good Owners Guide?

Many folks with dogs go into ownership unsure of themselves. They don’t know if they are handling or interacting with their dogs properly, and when their puppy or adult dog starts doing a behavior they don’t like, many owners are unsure how to address that. Often the interventions they attempt don’t achieve much, or even make the problem worse.

As we’ll talk about in more depth later, those feelings are natural, and in good part a consequence of a common cultural misconception: we often don’t think of dog ownership as a skill that needs to be learned, just like sailing, woodworking, or horseback riding (indeed, it could be argued that dog handling, rearing, and training have even more nuance – and consequences – than those skills). Just think about how we see dogs in movies and TV: the protagonist will leave their dog home alone all day with no consequences, feed them scraps with no consequences, never has to train them to not bark at guests, chew furniture, steal food, etc.

As a result, we often bring our dogs home without having fully learned how they think, why they do what they do, and how our interactions with them influence their behavior. Indeed, we often don’t know what we don’t know, and only realize we may be missing something when we run into behavioral problems.

That knowledge gap is not for lack of resources: there are tons of fantastic books, classes, trainers, online materials, etc. out there, in every medium and at every level of engagement; you can see a tiny fraction of them on our further resources page.

Rather, because we culturally often don’t talk about dog ownership as a skill that requires learning, many owners never start their educational journey. They don’t know where to start, and nobody is telling them why it’s so important, what they need to learn, and what the benefits of learning are (and consequences of not learning).

Consider a sobering statistic: several studies have shown that only around 5% of dog owners in the US take a single class.[1]

Most owners truly mean well – they sincerely want to give their dogs good, rich, healthy lives – they just don’t know how or where to start, or that they need to start.

That is where the RCO Primer, and accompanying RCOC, are intended to come in.

In the RCO Primer, we try to survey many of the topics that every dog owner needs to be familiar with. The goal is not for you to learn or memorize all this. As we’ll make clear, the only way to learn these concepts is through actual practice, and that means taking classes and working with a trainer – written resources will never be enough.

Instead, our goal is to start owners off right, in three ways:

- Help you understand the need – and benefits – to learning! To show you that learning how to understand, handle, train, and care for your puppy will produce an infinitely richer, healthier, safer, and less stressful life for you and your dog

- Start you off right with at least some basic familiarity with foundational concepts

- Encourage you to go on to read books, take classes, and work with trainers. We need to shift that 5% statistic above, and get more owners into the wonderful ‘educational pipeline’ that is out there

With any luck, the RCO Primer, and accompanying RCOC, will help achieve the above, giving you a map, a point of reference to come back to, and starting you on a clearer, more confident learning journey to becoming a stronger, happier dog owner.

[1] Stepita, ME; Bain, MJ; Kass, PH; Journal of the American Animal Hospitalization Association 2013 found only 4.7% of dog owners attended a single class; the APPA (American Pet Products Association) National Pet Owners Survey seemed to independently confirm this finding in 2022 (5%) and once again in 2023 (6%).

How to use the Guide with the RCOC

Summary: How to use the RCO Primer with the RCOC

- New dog owners do NOT need to read and memorize everything, all at once! You are meant to:

- Take the RCOC and refer back to this (each question links to the relevant chapter), to learn as you go. That is how the RCOC exam is designed, to help you digest and contextualize these concepts.

- Learn this material – alongside books, classes, and trainers – over the first few months and years with your dog.

- The RCO Primer and RCOC exam are meant only to START you on your learning journey. Per Aside #2 below, they are meant to make you more aware of what every responsible owner MUST know, thereby – hopefully – encouraging more owners to go on to pursue books, take classes, work with trainers, and try out sports and certifications like AKC CGC.

As you may notice, the following Sections and Chapters cover a lot of material – and that might be more than a little intimidating!

Fortunately, you are NOT meant to sit down and read, study, or memorize all the content in this Primer. These are concepts we expect you to learn and practice over the first few months and years with your dog.

Rather, here is how the Primer is intended to be used:

Alongside the RCOC as a reference, to learn as you go.

As we lay out in the RCOC exam, we built the RCOC around real-world scenarios, each of which is linked to chapters in the Primer. The idea is for you to (1) read a scenario; (2) look up those chapters with the scenario in mind; and (3) go back to now answer the question. That learning process gives you a better context for the concepts we cover, and breaks up learning into more digestible pieces.

Ultimately, our intent is NOT to try to teach you all of these concepts; rather, our goal is to make you to engage with these concepts; to realize how important they are, and thereby encourage more owners to start their learning journey.

As a reference and resource to START you on your learning journey

Even if and after you pass the RCOC, our aim with both the RCO Primer and RCOC exam is to start you on your learning journey. We hope the Primer will be a resource for you to continue referring to, as well as a map of the concepts you must go and learn through your continuing educational journey:

- Reading Books

- Taking classes

- Working with trainers

In practical terms, here is how we recommend proceeding:

Give it a cursory browse

Don’t stress about reading it from front to back – give it a browse, and check out topics that catch your eye/strike your curiosity. Because so many themes and principles are common across topics, you’ll be amazed at how much your mindset and intuition will start to shift even with just a bit of exposure.

Dive into the RCOC, using this Primer as a companion

Then, we recommend giving the RCOC exam a try. The RCOC (Responsible Canine Owner Certification) exam is comprised of real-world scenarios where we give you a few options and ask you what to do.

For each question, we tell you what the relevant Primer chapters are:

The idea is that you should read the question, and then – assuming you don’t know the correct answer – go to the relevant Chapter to help.

We believe that with a concrete scenario in mind, you’ll have an easier time digesting the material. Rather than dry facts, you have an actual situation – that you might encounter and need to be able to handle in your own life – to apply the concepts too.

That, we hope, makes learning more fun, aids comprehension, and improves retention.

There’s no time limit, and you can take the test as many times as you’d like – so don’t stress!

Continue on your educational journey with other resources, and come back to the Primer as a reference

As we’ll discuss much more in later Chapters, the RCOC and Primer are meant to start you on your learning journey, hopefully convincing you how important these topics are and encouraging you to go on to tap into the greater world of educational resources out there, ranging from books and online resources to in-person classes and trainers.

To help you, we keep a database of Further Resources updated with recommendations for you to continue your education once you pass the RCOC.

Even after you go off to those further resources however, we want the Primer to always be there for you as a reference. You can always come back and read sections or chapters that you feel less knowledgeable in, or help identify the gaps in what you might know.

Aside #1: Overarching themes

While all the chapters that follow can make it seem like there’s a lot to learn as a dog owner, what you’ll find is that best practices tend to be tied together by a few consistent themes, threads that run through everything. As you learn, you’ll start to see the same principles applied again and again in different contexts.

The more you learn and practice, the more these themes will become intuitive to you; you will start to rewire how you think as a handler, such that you more naturally know what to watch for and how to interact with your dog.

Below, we briefly mention some of these ‘themes.’ Don’t worry about learning or ‘memorizing’ them now: as you read through the Primer – and learn from other sources like books, classes, and trainers – we will come back to them again and again. For now, we just want to call your attention to them, to look out for later.

Pay attention to your dog; learn to read her language and emotions

The more you pay deliberate attention to your dog, watching how she interacts with the world, the more you will gradually become able to ‘read’ her, to tell what she is thinking, to anticipate how she will react to things, and to see what she will do before she does it. That ability to read your dog not only deepens your bond, it also makes living and working with your dog much easier; everything from socialization to training is made enormously faster, easier, and more fun if you’re able to respond to your dog’s mental state, rather than simply following a recipe. Your dog, by the way, will be doing the same – learning how to read you, to gauge how you are feeling. That is part of what makes them such wonderful partners.

First and foremost, it’s about helping your dog understand what you want

As humans, we tend to project our own understanding onto our dogs: when they act out or do things we don’t like, we think they are ‘misbehaving,’ as if they know that their behavior is wrong. Most ‘undesirable’ behavior to us is normal dog behavior, we just don’t like it; barking, jumping, and begging are all normal doggie behaviors. There is of course a big part of training that is coaxing your dog to do things they don’t want to do even when they know they should – particularly during rebellious ‘teenage periods’ (Chapter 1-16) – but before that the first step is always teaching your dog what you even want them to do.

Remember, your dog does not have the context you do! When the mailman comes they don’t know that that is a mailman, who has every right to be there. When you run the vacuum they don’t know that is a vacuum, a safe machine that you are controlling. When you go to the store they don’t know that strangers approaching them mean no harm. When they first come home they don’t understand that ‘indoors’ is not an appropriate place to potty.

Your first responsibility with your puppy or adult dog in any situation is teaching them to understand what is going on, and how they should behave. If you’ve built a strong relationship with your dog and good behavioral foundations (see below), they will try very hard to do the right thing, they just have to know what the right thing is. Over time, try to learn to look at every situation through your dog’s eyes.

Be clear and consistent in what you ask of your dog

A big part of teaching your dog the ‘right’ way to behave in any given situation is consistency. Too many dog owners will, for example, throw commands out without any follow up – which their dogs will inevitably blow off – and then panic when their dog doesn’t comply in an emergency. You can’t ask a dog to behave a certain way some of the time; remember, they don’t have the context you do. Anything you want to teach your dog, you have to be consistent.

When we start to talk about training practices in Section 2, You’ll learn to not ask your dog to do something they’re not going to do; and when you do ask them to do something, making sure you pair it with sufficient incentives, particularly if it’s in a challenging context (such as with lots of distractions). We’ll talk about this concept in much more depth in later chapters.

You are the guardian, the teacher, you define and teach what is appropriate and inappropriate behavior – your dog has no other way of knowing

Getting your dog to understand what to do requires that you remember: you are the teacher, the guardian, you know what is right and wrong behavior, the puppy does not. If your puppy is whining, should you comfort and play with them? That depends: if they have been fed, hydrated, recently pottied, and have gotten plenty of physical and mental stimulation from you today, then they are fine, they may need to learn to occupy themselves.

At the same time – per above – you need to listen too. You define what acceptable and unacceptable behaviors are, but you need to define those with an understanding and respect for your dog’s mental and physical needs and biological imperatives.

In general, remember: your dog has no way of knowing on their own what is appropriate and inappropriate behavior; there is no gene telling them ‘don’t jump on strangers,’ ‘don’t chase children,’ or ‘don’t be afraid of trash cans.’ You need to show them and teach them those things.

Build your dog’s trust in you – show them that you are in control of situations; if you succeed, they will look to you when they are afraid or uncertain, rather than trying to handle situations themselves.

Filling that role as a teacher, a guardian, requires that your dog trusts that you always know what is going on, will always protect them, and will always have the situation in hand.

For example, if your dog starts to become reactive to other dogs – barking and lunging at them when they approach – part of that is because they feel the need to protect themselves. Part of teaching your dog how to handle situations like those will be teaching them to rely on you and your judgment, rather than feeling a need to protect themselves.

Again, dogs lack the context we have – things happen all the time around them that they don’t understand. If your dog trusts that you are present and aware and in charge, it will help them weather those stressors.

You need to understand and meet your dog’s basic needs

As the dog’s guardian, it is your responsibility to make sure your dog’s needs are met. By owning dogs we deprive them of agency: we control where they are allowed to go, and what behaviors we deem appropriate.

As a result, dogs are often limited in what forms of enrichment they are able to access on their own; they rely on us to give them access to places to run, smells to explore, ‘acceptable’ objects to chew, etc.

That means it is your responsibility to ensure your dog gets enough physical activity and mental enrichment. Failing to do so is the root of many bad behaviors: an under-stimulated dog can find other ways to get their energy out, like tearing up your house or barking uncontrollably.

Build foundational skills

Throughout the primer we focus on specific behaviors most owners will want to cultivate, such as not barking at or jumping on visitors, not pulling on the leash, and following cues we ask for like Sit and Down.

What you will find however is that all of them serve a greater purpose than simply obedience behaviors: they start to build your dog’s core capabilities. Things like emotional regualtion, handler focus, problem-solving ability, adaptability to new situations, resilience/ability to remain calm, etc. We review these specifically in Chapter 2-27, but it’s worth understanding that every hour you put into working with your dog pays double dividends: not only do they learn the specific thing you’re working on with them, they are also building up those underlying capabilities that will make them happier, stronger, and more fun companions over the course of their life. That also means that the more you work with your dog, the easier it gets over time. As they build those foundational skills, they will learn faster and be more learning-savvy over time, and their behaviors will become more reliable and resilient.

Watch how you interact with your dog: learn to see the implicit positive and negative associations made from every one of your actions

In Section 2, we will formally introduce the concept of reinforcement. The basic idea is that when you reward – with say praise or treats – or penalize – with yelling or taking away something your dog wants – a behavior, you are implicitly encouraging or discouraging that behavior. What you will find throughout the primer is we are, often unintentionally, ‘reinforcing’ and potentially ‘punishing’ our dogs’ behavior, nearly every time we interact with them.

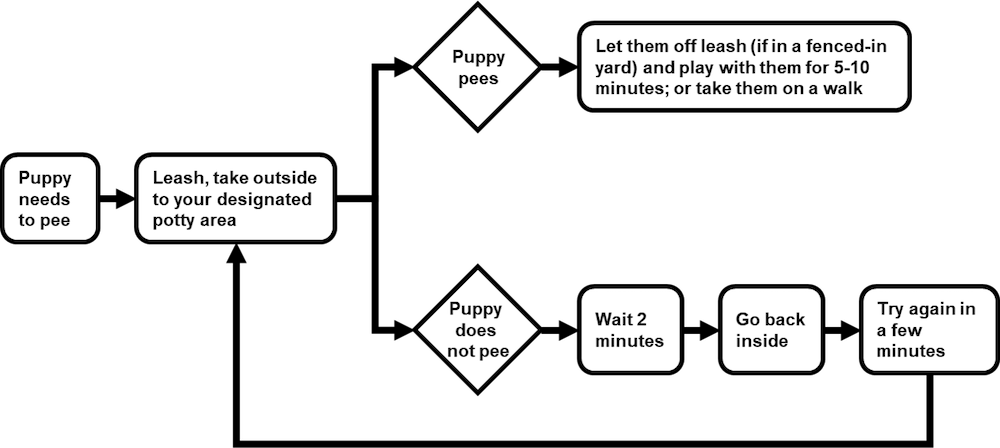

For example, if you take your puppy outside to potty, they do their business, and you take them back inside, you may have inadvertently punished the prompt pottying; the puppy did their business outside but didn’t get to explore, and as a result the puppy learns that pottying means heading right back inside the house and thus will delay pottying as long as possible when first taken outside. A puppy who loves being outside will feel punished for having eliminated appropriately.

As you apply the content in this primer, you will start to learn to see reinforcement everywhere, you will – hopefully – get in the habit of asking yourself, whenever you do something, ‘what am I reinforcing?’ As you build that consciousness, you may start realizing how you interact with your dog is often training. Best of all, you’ll often find that those changes to your normal, minute-by-minute interactions with your dog have just as much impact on their behavior as do your formal training sessions.

Build a collaborative relationship with your dog

Your time with your dog will be substantially more joyful and fulfilling if it is collaborative, rather than transactional. Far more dog-owner relationships fall into the latter category than owners realize. If your dog ignores your cues without any sign of guilt, then does she really view you as a partner? A healthy relationship with your dog is one where they learn that life is more fun when you work together. When they ‘work’ – i.e. follow cues reliably – they get praise and rewards, all the stimulation of playing a game (following the ‘rules’ and doing the right thing), and – most enjoyable of all – the profound joy that dogs and humans both get from camaraderie, from working deliberately as part of a team. Teaching your dog ‘obedience behaviors’ is about working together as a team. Owners who build that collaborative relationship, where your dog looks to you for guidance and loves to work together, will find a far deeper connection with their animals. A collaborative dog trusts you, sticks by you, and wants to do things with you.

Dogs are not little humans

Often our biggest mistakes come from projecting our instinctive primate inclinations onto canines. Despite millennia of co-evolution, we still have very different evolutionary roots. As a result, there are many behaviors we find so natural, so automatic, so intuitive that we take them for granted, not even realizing that we do them. Often however, those behaviors lead us to do wrong by our dogs, often fatally so.

As some examples: humans can sweat from their whole bodies, an extreme rarity amongst animals, making running on a sunny 75ºF day comfortable to us, but potentially deadly for dogs (who pant and sweat only from their paws, which might be on hot pavement). As primates we are programmed to find touch, proximity, smiling, and eye contact comforting, whereas canines can find those gestures threatening and confrontational. Dogs digest the world through scent far more than we do, while we are satisfied consuming the world with our eyes; for us, watching TV or reading a book is sufficient daily entertainment, but a dog needs open-ended outdoor exploration. And so on. We explore this concept throughout the primer, but particularly in Section 4: Dog Physiology and Psychology.

Aside #2: The term dog ‘owner’

Why we use the term ‘owner,’ and what’s wrong with that term:

Throughout this primer – and our site at large – we use the most common vernacular term “dog owners” to refer to a dog’s primary caretakers (i.e., you, the reader). We use that term because our primary goal is to be accessible and understandable to new dog owners who have not yet started their educational journey. Dog ‘owner’ is currently, by far, the most widely-understood term, and therefore minimizes any chance of confusion for the casual reader browsing this Primer.

We’d like to mention, however, that we do not like the term ‘owner,’ because its connotations fundamentally mis-represent the relationship between dogs and their caretakers. ‘Owner’ can imply that your dog is a sort of object, or subservient; that they ‘owe’ you something, that they are there to fulfill your needs – or that they even know how. It propagates some of the cultural misconceptions we highlighted earlier:

As a result, we much prefer terms like “guardian” – which is increasingly popular – “caretaker,” “partner,” or “teacher.” As you’ll see, those terms more accurate reflect your relationship with your dog.

For now, in the interest of clarity and accessibility to a broad audience, we have opted to compromise and stick with the more widely understood term “owner,” but as you’ll learn it is not the best language to describe your connection to your dog.

Introduction️:

What it means to be a good owner

Goals of the Guide: building a better, easier life with your dog

Welcome to the Good Owners Guide to Dogs! Over the sections and chapters that follow, we will aim to:

- Introduce you to foundational concepts on how to appropriately and effectively raise, handle, care for, understand, and communicate with your puppy or adult dog

- Start you off on your learning journey, beginning with the Guide and taking you into the incredible world of books, classes, trainers, and online resources out there!

As you’ll see, taking a bit of time to learn how your dog works and how to build a healthy, sustainable relationship with them will make every part of your life together easier, more intuitive, less stressful, more fulfilling and more fun!

Cultural misconceptions: Unfortunately, many of us go into dog ownership with some misconceptions around who a dog is, what they need, and ‘how they work.’

Before going further, we should start by recognizing some of the mistaken assumptions many of us have going into dog ownership, as a result of common cultural myths about dogs. These misguided beliefs, if you don’t recognize and move past them, can have a profoundly negative effect on both you and your dog’s life:

Popular misconceptions

- Dogs are passive: the idea that they’re there to wait around for us calmly all day while we’re at work, and then come cuddle with us in the evening when we’re ready for it. That they don’t have rich inner lives, and their own needs for physical, mental, and social enrichment.

- Dogs are “being bad:” when they do something undesirable (to us) – like chewing on your purse, or peeing in the house, or barking at visitors – we say they’re being a “bad dog,” as if they intend something bad. When we do that, we are assuming that they have already somehow learned human manners and norms, often when we haven’t put in the work to teach them. As you’ll learn throughout the Guide, that’s most often not the case: your dog is probably not deliberately ‘being bad,’ they just either (a) don’t have the context you have (how is a puppy supposed to know the difference between “inside” and “outside” without being taught that carefully by you? Or what a mailman is when they come into your yard?); and/or (b) have some need, stress, or confusion that isn’t being addressed. In the rare cases they are deliberately ‘mis-behaving,’ that is nearly always a consequence of a more fundamental problem in their lives that needs to be addressed (by you).

- Dogs should “obey” us: that we are their “master,” that when they follow our “commands” they should do it out of obeisance and duty, as opposed to their trust in us, fondness for us, desire for us to be happy, and desire for social acknowledgement, to be part of the family/society. When you ask a friend at dinner to pass the salt, your spouse to wash the dishes, or a stranger to give the time, are they “obeying” you? Or have they learned from childhood that ‘this is the appropriate way to participate in society’ and are simply doing what they feel and have learned is the right to do?

- Dog guardianship is mostly about logistics: many of us think: “if I want a dog, I go to the shelter/breeder, get a dog, then just feed them and take them for walks.” Nowhere in that sequence is: “I need to learn something, about how to understand, care for, and interact with a dog.” Consider an analogy to sailing: no one thinks they can just get in a sailboat and sail away without first learning how to sail; yet when it comes to dogs – living beings with a full range of complex needs, emotions, personalities, and agency – we somehow think we need little or no preparation or knowledge.

- Dogs are simple-minded: we think they lack the breadth and complexity of emotions, social relationships, and cognitive processing humans have, as if in the evolutionary miniscule amount of time our species evolved separately from them we developed 99% different brains and capabilities. While dogs and humans are very different – and it is important to learn and appreciate those differences – they have many of the same root mental and social needs and behaviors that we do (especially if you don’t neglect those needs and let your dog’s ability to think and communicate atrophy).

- Dog training is a recipe book: pull lever X to get a dog to do Y, like robots. Of course dogs – just like humans – respond to rewards and aversive stimuli, but their psychology – in a given situation, what is rewarding? What is aversive? What is their understanding of the situation, and broader history and context? – is not a simple formula. For example, why is your dog barking and jumping at visitors? Is it because they are afraid of strangers entering their space? Afraid of unfamiliar people in general? Startled or confused by the unexpected visitors? Happy and over-excited to see new people? Protective of your family? To teach and interact with your dog in a healthy way, you need to learn how to listen to them, to figure out why they do what they do, and to communicate back to them.

As you’ll learn throughout this Guide, these common preconceptions are deeply flawed. Dogs are sophisticated beings with rich inner lives; they do things for a reason, and have physical, social, and mental needs that have to be fulfilled.

The greatest harm caused by the misconceptions above is that they tend to prevent us from learning how to appropriately understand and interact with our dogs. When you don’t understand your dog – their needs and their psychology – then they can start to feel like a black box: you just can’t figure out why they’re still pottying in the house, or hiding in their crate, or chewing on your furniture, or barking all day. You can quickly reach your wit’s end: everything you try either doesn’t work or makes the situation worse, you’re stressed and anxious for this creature you love, the internet is filled with all sorts of contradictory advice, and you just don’t know what to do or even where to begin.

For that reason, it’s critically important that, aside from any specific knowledge and practices you look to learn, you start from a good, accurate understanding of ‘what a dog is;’ that you have a grounding in their needs, experiences, and psychology, to help you interpret and seek the right answers to any challenges you experience. That is why, as we talk about next, the first and most important thing you need to learn is the right mentality for how you think about your dog.

How to be a good owner: the most important thing to learn as a dog owner is the right mentality. If you can develop the right mindset for understanding and living with your dog, your intuition will be more reliable, you will find your way more easily to the right information, and every part of your life together will be easier, more intuitive, less stressful, less work, more fulfilling and more fun.

As you embark on your learning journey – whether through this Guide or other books and resources – we want to highlight that even more important than any specific knowledge on how to handle particular situations is learning the right mentality for living and working with your dog. Learning how to think about your dog; how to have the right perspective on who your dog is, how to interact with them, and how to approach your relationship.

You’ll start to develop that mentality over time as you learn different practices and concepts, but here are a few ways of thinking you should start from:

- Look at every situation from your dog’s perspective – how is your puppy supposed to know that “pottying should be outside” – or for that matter how can they know what “outside” even is? How is that different from “inside”? How is your dog supposed to know what a mailman is, and that they’re allowed to come into your yard? Your dog doesn’t have the context that you, as an adult human, have. Where it matters, you will have to carefully, thoughtfully, and empathetically teach it to them.

- Understand your dog’s needs – any dog, like any person, needs a sufficient amount and diversity of physical, social, and mental stimulation (and, unlike a person, many of those needs they can’t meet on their own inside a typical human house). If those needs aren’t met, they can – understandably – become anxious, depressed, hyperactive, belligerent, or destructive.

- Communication is crucial, listen to your dog – your dog can and will tell you what they are thinking and what they need; the trick is paying attention and learning how to understand what they’re saying.

- Teaching your dog is not a recipe book! You don’t “do X to get Y;” your dog’s behavior in a given situation depends on their personality, their history of experiences, their current mental state, the situational context, etc. You’ll find life with your dog easier and more fun when you learn how to read and understand what your dog is experiencing, and use that understanding to guide how you communicate with them.

- A “good dog” comes from a good owner; YOU need to learn, before your dog can – the first reaction of most people whose dog exhibits an ‘undesirable’ behavior (barking, destroying shoes and furniture, chasing children, etc.) is to take their dog to a trainer and ask them to ‘fix my dog.’ That will never work: your dog isn’t ‘being bad,’ they are either under some form of stress or have developed some behavioral pattern that is being or has been reinforced at home. At the end of the day, how you interact with your dog, the situations you put them in and the way you treat them, will dictate the behaviors they develop. A trainer is there to teach you how to read, understand, manage, and interact with your dog in a healthy way, in addition to any work they do to directly help your dog.

- Your dog has limits – given what we ask of them, dogs are incredibly understanding and patient with us. We regularly leave them home alone all day without explanation, expect them to stay calm and quiet while we throw a loud party, or expect them to tolerate unfamiliar people or other dogs invading their space without hesitation. As you ‘layer stress’ onto their lives, they not only suffer internally, but will eventually manifest destructive behavior. Going back to bullet #1, “look at every situation from your dog’s perspective,” always understand the stress you’re putting them under, mitigate it where possible, know their limits, and don’t put them in situations they can’t handle.

- You can build your dog’s capacity – as you’ll learn throughout the Guide, working with your dog in a healthy, appropriate way, on things like socialization, tricks and ‘obedience,’ play, etc., helps build their confidence, resilience, self-control, problem-solving capacity, and other ‘core capabilities.’ That makes them more happy, well-adjusted, and stable, and deepens your relationship.

If you start approaching your interactions with your dog with mentality above, you will find:

- You will gradually start to read and understand your dog better

- Your relationship with your dog will be richer and more fulfilling

- You will have an easier time spotting and diagnosing problems, and finding your way to the resources and people you need to help address them

- You will feel less often lost or frustrated

What do I need to learn? Dog ownership isn’t just about providing food and water; you need to learn how to handle, raise, care for, listen to, understand, and interact with your puppy or adult dog.

As mentioned above, the first and most important thing we want you to take away from this – or any – source of dog learning is the right mentality and approach to life with a dog. Of course, however, you do also need to learn some concrete knowledge on how to handle, raise, care for, understand, and interact with your puppy or adult dog. You will find life with a dog much easier, less stressful, less work, and more fun for you both if you learn at least some foundational concepts. Concepts like, for example:

- Socialization – How to introduce your puppy or adult dog to new sorts of people, places, objects, sounds, surfaces, other dogs/animals, etc. in a thoughtful manner that will make them more confident, resilient, and well-adjusted, and avoid or mitigate developing reactivity that can be stressful and dangerous for them and you both.

- Errorless learning – How to avoid the development of undesirable habits by anticipating and preventing your puppy from engaging with them in the first place.

- Potty training – How to minimize puppy accidents and potty train as quickly and reliably as possible by limiting your puppy to an age-appropriate, gradually expanding ‘circle of freedom’ and taking them out at sufficiently conservative intervals.

- Separation anxiety – How to slowly acclimate your puppy or adult dog to the occasional (or frequent) necessity of being left alone, in a way that helps them tolerate that experience without spiraling into a panic, barking continuously, or redirecting their stress into destructive behaviors.

- Crate training – How to make the crate a calm, joyful place for your puppy, a sanctuary where they can feel safe and secure in situations where they are stressed or over-excited, as opposed to a ‘punishment’ or otherwise stressful experience.

- ‘Training’/associative learning – How and why to teach your dog behaviors, including both fun ‘tricks’ and helpful ‘lifestyle behaviors’ like Settle, recall/Down, etc., to provide wonderful mental enrichment, deepen your collaborative relationship, build their confidence, and provide a toolset to help them safely and healthily navigate the human world.

- Unintentional reinforcement – Ways we often accidentally reinforce ‘undesirable’ behaviors, such as taking a long time to potty, jumping on people, chasing children, barking, or stealing food – and how we can stop.

- Physical and mental activity – How to understand and most easily meet your dog’s needs for physical, mental, and social stimulation.

- Basic husbandry – How to approach nail trimming, grooming, ear cleaning, tooth brushing, etc. – and why that husbandry matters.

- Genetics and breed effects – How to think about common heritable traits and behaviors – such as herding behavior, prey drive, guard behavior, and energy – as you either identify a dog that may or may not be suitable for your life circumstances, or seek to better understand the dog you already have.

Why should I learn? Learning a few foundational basics of how to live happily and healthily with your dog will massively improve you and your dog’s quality of life.

Investing just a modest amount of time in learning how to live and work with your dog in an appropriate, effective manner yields enormous dividends throughout your life together:

- Give your dog a better life – learning how to listen to and communicate with your dog means they’re more likely to have their physical and mental needs met, not be put in inappropriately stressful situations, and have a richer and more fulfilling life at home with you.

- Build your dog’s confidence, resilience, and self-control – well-conducted socialization, training, and general everyday interactions all help build your dog’s confidence, their ability to control their emotions, their ability to bounce back from adverse situations, and other fundamental capabilities that help them better navigate life.

- Develop good ‘lifestyle habits’ – wouldn’t it be wonderful not having your dog jump on guests, steal food, chew on furniture, pee in the house, or bark at other people and dogs? Learning how to teach your dog appropriate behaviors and outlets for their energy, how to live in our human-centric world, makes your life a lot easier!

- Avoid or better manage your dog’s stress, anxiety, or reactivity – limited or improper socialization, poor handling, under-stimulation, etc. can all lead to stress that is detrimental to your dog and behaviors that are destructive or dangerous to you.

- Reduce YOUR stress – few things are more stressful than seeing the dog you love stressed, anxious, or ‘acting out’ (chewing furniture; barking manically at strangers, other dogs, or children; digging up the yard; etc.) and not knowing what to do, how to stop it, or how to help them.

- SAVE you time – while learning and practicing the basics of dog raising, handling, and care takes some up-front investment on your part, we promise it will save you enormous time and energy down the road, in the form of bad habits you avoid your dog forming; not having to ‘manage’ your dog as actively or constantly; dealing with less leash-pulling, barking, accidents, etc.; fostering a more confident, stable, resilient, and less anxious dog; being able to put your dog in more situations with fewer concerns; and so forth.

- Be LESS work – at first, as you learn new concepts, it will seem like there is a lot to keep track of. We promise though, as you start to put things into practice – and especially if you have the chance to work in a class or one-on-one with a professional trainer – it will become habit, and you will find living and interacting with your dog easier and more intuitive.

- Have more FUN together – learning how to work with your dog both let’s you do more with them (take them more places, involve them in more things, and do more interesting things with them at home) and makes your time together more fun.

- Build trust – working and interacting deliberately and conscientiously with your dog, learning to listen to and communicate with them, builds their trust in you and your judgement, and can often transform your relationship for the better.

- Have a profoundly richer, more intimate relationship with your dog – every day we see owners who have lived with their dog for 10 years, who love their dogs deeply, and yet who are entirely oblivious to how to their dog actually feels and what their dog is trying to communicate. Too few of us actually learn to listen to our dogs, to watch and observe them rather than projecting assumptions onto them. Learning to understand and communicate with your dog opens up an entirely new world for the two of you.

We promise, you will never regret learning more about your dog!

The goals of the Guide: We created this guide to provide companion dog owners with an easier starting point, to lower the barrier for owners to begin their learning journey, and to better set owners up for success. We promise that if you just start to learn more about how your dog works and how you can better engage with them, your life with your dog will be easier, more fun, and more fulfilling!

While there is an abundance of incredible educational resources out there – everything from local puppy and intro classes to introductory books and excellent online videos and courses – the reality is life is busy. Interviewing hundreds of owners as part of this project, we’ve found that the vast majority sincerely want to learn more about how to understand and interact with their dog, but it can be hard to:

- Parse through and navigate all the resources out there

- Figure out what you actually need to learn

- Find time to sit down and engage with resources

To us as trainers and dog professionals, a few 15 minute videos or a once-a-week class may not seem like a lot, but for a pet owner at the end of a long day of work, running errands, entertaining the kids, making dinner, etc. – sitting down to digest a video or hopping in the car to go to a class is a significant barrier. That is one reason why as many as 95% of dog owners never take a single class or work with a trainer.[1]

That is why we created the Guide: to help steer more owners to start their learning journey. The design and strategy of the Guide were crafted specifically to:

- Lower the barrier to learning: make it easy for owners to hop in and out and engage with concepts whenever and however they feel ready to.

- Expose owners to core concepts: familiarize them, usually for the first time, with critical ideas like socialization, separation anxiety, physical and mental activity needs, associative learning, breed/family history effects, etc.

- Show the benefits of learning those concepts – how they not only make your dog’s life more joyful and less stressful, but will save you time, energy, and stress and profoundly deepen your understanding of and relationship with your dog.

- Steer more owners into a broader learning journey – get a higher percentage of them into classes, trainers, books, and online resources. We consider our core mission to be “getting more owners into the ‘educational funnel’.” To systematically improve outcomes for dogs, we need to raise that 5% number!

- Change owner mentalities – far more important than any specific facts or concepts, we want to shift how owners think about their dogs. By explaining every concept from the dog’s perspective, grounding practices in the needs and psychology that underly them, we aim to get readers in the habit of thinking of their dogs in that way.

If you’re curious, you can see more about why we created the Guide and how we designed it at the article here.

[1] See broader article here; data reference: Stepita, ME; Bain, MJ; Kass, PH; Journal of the American Animal Hospitalization Association 2013 suggested only 4.7% of dog owners attended a single class; the APPA (American Pet Products Association) National Pet Owners Survey seemed to independently confirm this finding in 2022 (5%) and once again in 2023 (6%).

The learning journey: This guide is just a starting point, to help guide you towards taking classes, reading books, and working with a trainer!

Per our goals above, the aim of this guide is to help shepherd more people into the learning journey that every dog owner needs to go through – for the benefit of both them and their dog!

The dog owner learning journey

- This Guide: As a starting point, you can browse our Good Owners Guide to Dogs. Note you should not try to read the whole thing, front to back. As we’ll talk about in the next toggle below, the Guide is meant as a reference, a map, an anchor – to dip your toe in, see what sorts of concepts you should learn (and why), and start getting a handle on things. You can spend as much or as little time with it as you like before moving on to other resources, and you can hop into any chapters or sections most interest you.

- Take an intro/basics course: Find a qualified professional trainer near you and take at least one 6-12 week introductory course, either in a group class or one-on-one. While it might seem pricey, we promise it will very quickly save you time, energy, stress, and money (and make your relationship to and life with your dog more fun), as we laid out in the ‘benefits’ toggle above. Be sure to find a reputable trainer that centers their methods on the dog’s emotional state; for tips on how to identify a qualified trainer see Chapter 2-23. If you live in an area where there are few in-person training options near you, note that many great trainers across the country offer virtual sessions, in addition to many organizations that offer recurring virtual classes, either of which can be extraordinarily effective and beneficial.

- Read some intro books, watch some online seminars, videos, and courses, and take some one-on-one trainer sessions: As you start to get some basics down, you’ll want to dive deeper into areas that are of most interest and concern to you, based on your dog’s needs and your lifestyle. Maybe that’s better understanding separation anxiety and how to manage it; developing better public access skills and behaviors; dealing with some over-arousal or reactivity issues; or finding your way to sports and activities that will help provide the physical and mental enrichment your dog needs while being maximally fun for you too. There are tons of amazing resources out there. For a place to start, you can check out our ⭐list of other educational resources to check out⭐!

How to use the Guide: do NOT try to read and learn everything all at once. Use it as a reference and a jumping-off point.

To get the most out of the Guide, we recommend approaching it as:

- A starting point: as we laid out above, the goal of the Guide is to make it easier for you to start your learning journey as a dog owner. By introducing you to some key concepts and how they relate to your life with your dog, we hope to set you up better for success and steer you into the wonderful ecosystem of books, classes, online videos, in-person trainers, and other amazing resources out there. See previous toggle for more on this journey.

- A reference: as you continue your life with your dog, learning from different places and from your dog herself, come back to the Guide as a reference – to remind you of concepts you might’ve forgotten; to help you make sense of new behaviors you’re observing, or unfamiliar concepts you hear about; and to get a ‘map’ or checklist of topics and practices you haven’t learned about yet and might want to look more into.

- NOT a beginning-to-end read: don’t worry about or try to ‘slog through’ the Guide. It was built to be a large, comprehensive resource for you find what you need in all sorts of situations. Do NOT try to read it beginning to end. Instead, just hop into any chapters or sections most interest you!

- NOT your sole source of learning: our firm belief is that no text-based resource can teach you how to work with a dog; ultimately, as we laid out in ‘the learning journey’ toggle above, you’ll need practice, ideally alongside a qualified professional trainer in a class or one-on-one setting, or at the very least through online videos or courses (you can some recommended resources here).

Don’t stress! As you review the Guide or take classes or read books, at first it can start to feel like a lot. Don’t worry! It will be easier than it looks, and it’s a learning journey – it’s OK to make mistakes!

Ironically, you may find the more you learn, the more you realize how much you don’t know about how to understand, communicate with, and care for your dog. Don’t worry! While it might seem like a lot to learn at first, remember:

- It will be easier than it looks!

While there are many concepts to learn, and you’ll find that putting them into practice is even harder than learning the concept, we promise that learning and practicing better handling and care will be easier than it looks, primarily because the same themes and approaches come up again and again – good practices in socialization, crate training, associative learning, etc. all draw from the same understanding of your dog’s needs and psychology, so each thing you learn will make future learning and practices easier. Over time you’ll build a better and better intuition for how to interact with your dog in all situations – and isn’t that something to look forward to!

- You will make mistakes, and that is OK!

Any trainer worth their salt will tell you that no matter how much experience they have, they are still always learning new things. Learning how to understand and work with dogs is a lifelong journey. Will you make mistakes – accidentally reinforcing an undesirable behavior, messing up a socialization experience so that your puppy is now afraid of something, or putting your dog in a situation you shouldn’t have? Yes, absolutely. Will that ‘ruin’ your dog or your relationship with them? No! As long as you’re on the right path, and adopting the right mentality – paying attention to your dog’s emotional state, looking at the world from their eyes, etc. (see above) – you will do a great job with your dog over the course of your life together. With the right intentions, you will, over time, find your way to the right learnings and practices, understanding and communicating with your dog better and better.

Broader learning resources

Summarizing the previous chapter, we created the Good Owners Guide to help owners start their journey learning how to better handle, raise, care for, interact with, communicate with, and understand their puppy or adult dog.

As we highlighted in that chapter, our core mission is to not only familiarize you with foundational concepts and provide you with a solid reference point, but to also steer more owners into the fantastic broader educational ecosystem out there – the wonderful but messy world of amazing books, classes, in-person trainers, videos, and many other resources. Interviewing hundreds of owners as part of this project, we found that despite the many resources out there, the barrier for many to getting started is often too high; people’s lives are busy, and many great resources today can be difficult for new owners to navigate and take advantage of. The result is that the overwhelming majority of dog owners never begin their learning journey, never take a class or learn from a trainer.[1]

To that end, we tried to make the Guide a comprehensive but accessible resource; a single ‘jumping off’ point you can use to familiarize yourself with concepts, steer you towards more in-depth resources or in-person classes or trainers, and come back to later for reference as you learn. From the get-go though, we want you to be aware of the wonderful broader ecosystem of resources out there that you should soon begin to explore:

💡Curated list of recommended educational resources for companion dog owners

Specifically, we strongly recommend that every dog parent, in addition to perusing the Guide:

- Take at least one 6-12 week intro/basics course with a qualified local trainer

- Read one or two introductory books, and/or watch an online video series (some suggestions)

For more information on how to approach each of those steps, see the ‘learning journey’ toggle of the previous chapter.

And if you run into challenges or have questions, please don’t hesitate to reach out to us – try hello@goodowners.dog. As a predominantly volunteer team we can’t commit to responding right away or solving every problem, but we’ll always do our best to steer you in the right direction. Our entire lives are committed to helping dogs, and that only happens if we can help you – the parent who loves and has committed to caring for your furry friend. Per our mission: “better educated owners, better lives for dogs.”

Have fun and happy learnings!

❤️🐾 The entire Good Owners team

[1] As few as 5% of dog owners in the US ever take a single class or work with a trainer. See broader article on this subject here; data reference: Stepita, ME; Bain, MJ; Kass, PH; Journal of the American Animal Hospitalization Association 2013 suggested only 4.7% of dog owners attended a single class; the APPA (American Pet Products Association) National Pet Owners Survey seemed to independently confirm this finding in 2022 (5%) and once again in 2023 (6%).

The terms ‘owner’ and ‘obedience’

An important aside on two commonly-used terms.

Why we use the term ‘owner,’ and what’s challenging with that term

Throughout the Guide we use the most common vernacular term, “dog owners,” to refer to a dog’s primary caretakers (i.e., you, the reader). We use that term because our primary goal is to be accessible and understandable to new or novice dog owners who have not yet started their learning journey. Dog ‘owner’ is currently, by far, the most widely-understood term, and therefore minimizes any chance of confusion for the casual reader exploring this Guide and, hopefully, starting to learn some core concepts.

We’d like to mention, however, that we would ideally prefer to avoid the term ‘owner,’ because its connotations fundamentally mis-represent the relationship between dogs and their caretakers. ‘Owner’ can imply that your dog is a sort of object, or subservient; that they ‘owe’ you something, that they are there to fulfill your needs – or that they even know how. It propagates some of the cultural misconceptions we highlighted in the earlier chapter.

As a result, we much prefer terms like “guardian,” “handler,” “caretaker,” “partner,” or “teacher.” As you’ll discover throughout this Guide, those terms more accurately reflect your relationship with your dog.

For now, in the interest of clarity and accessibility to a broad audience, we have opted to compromise and stick with the more widely understood term “owner,” but as you’ll learn it is not the best language to describe your connection to your dog.

Challenges with the term ‘obedience’

‘Obedience’ is another term this is useful for its broad understandability, but whose connotations can lead to a misunderstanding of how you relate to and work with your dog.

When most folks hear ‘obedience training,’ they think it is about ‘getting’ or forcing your dog to do what you say. In reality, ‘obedience’ isn’t about subservient compliance – it’s about your dog learning what to do, how to operate as part of a team/learning their role in your family, and trusting you when you ask them for something. When you ask a friend to pass the salt at dinner, your spouse to unpack the groceries, or a colleague to send you some documents, are they “obeying” you? Technically yes, but they are doing it out of social norms and consideration, not because you have ‘mastery’ over them.

Your dog isn’t your slave – they have their own agency. You are ‘in charge,’ you are the parent, in the sense that you have more experience, context, and perspective than they do, and building a healthy working relationship is, at its core, about building your dog’s trust in your judgement, which then translates to them following your cues. But it’s important to note that healthy, effective, relationship-building ‘obedience training’ is about showing your dog the ‘right’ way to behave and building their trust and confidence in you, as you would teach a child appropriate manners and how to treat other people, not ‘bending them to your will.’

That is also, for example, why we prefer the term “cue,” as opposed to “command.” It is about communication and team-work, not submission.

Section 1:

Puppy Phases and Socialization

Section 1 Introduction: Puppies don’t raise themselves, and the first two weeks and months are crucial

“Now that she’s housebroken, our new puppy is really not a lot of work, we take her for a walk twice a day and that’s pretty much it”

“Yeah she chews on furniture but that’s just what puppy’s do!”

“[after picking up her puppy in January] I’m pretty busy right now, but I’ll have more time in the summer to work on stuff like training”

[Talking about a puppy they brought home last month] “She’s doing great! We haven’t taken her out of the house yet but we’ll start going to dog parks soon.”

Through the chapters in Section 1, we will take you through some of the most important things you need to be aware of to set you and your puppy up for success. Before we dive in however, it’s worth setting expectations and addressing some common misconceptions new puppy owners often have.

The first weeks and months after you get your puppy are crucial! Experiences in the puppy period are essential to your dog’s behavior, health, and relationship with you later in their life. This period is not just about logistically ‘taking care’ of your puppy; this is a window where crucial socialization and training need to occur!

Damaging misconceptions about puppyhood: There are two common – and enormously damaging – misconceptions that far too many new puppy owners go into the experience with:

- “Puppyhood is (solely) about ‘taking care of’ my new puppy” – INCORRECT. While of course you need to meet your puppy’s basic needs for food, walks, vet visits, etc., puppy rearing is about more than logistics; it is also a critical period in which you must ‘socialize’ them, teach them critical skills like chewtoy training and crate training, build key capacities like confidence and self-control, and start behavioral training.

In the chapters that follow, we will take you through some of the essential things you must work on your puppy with, such as:

- Socialization (Chapters 1-2, 1-3, 1-4, and 1-5)

- Chewtoy Training (Chapter 1-7)

- Crate Training (Chapter 1-8)

- Separation Anxiety Training (Chapter 1-12)

- Early Behavioral Training (Chapter 2-26)

- And more

- “Whatever we don’t do now we can do later” – INCORRECT. All of the needs we described above – in particular socialization – are far easier in the first few weeks after you get your puppy. In the chapters that follow, especially Chapter 1-1: Puppy developmental phases, Chapter 1-2: Socialization basics, and Chapter 1-9: Errorless learning, we will show you in more depth why that is the case, but there are essentially two factors at play:

- Puppies have certain narrow developmental windows, periods where they are more receptive to e.g., socialization, that you need to take advantage of while you can.

- It is far faster, easier, and more durable to start off with good habits than it is to untrain bad ones. As we will see in later chapters, particularly Chapter 1-9: Errorless learning, it is much more effective to introduce your puppy to behaviors and experiences early on, before they have a chance to develop bad behaviors or responses, than it is to try and play catch-up later.

In both cases, some extra investment of time and energy now, in addition to setting your puppy up for success, ends up saving you a lot more time and energy later!

The bottom line here is that you cannot delay. You should plan to:

- Before getting your puppy, tap into resources – like this Primer, the associated RCOC exam, and an array of other resources (see Aside #2: Further resources) – in order to familiarize yourself with what you need to do in these first few weeks, so that you’re not wasting time scrambling to learn.

- In the first few weeks after getting your puppy, as we will lay out further in Chapter 1-1: Puppy developmental phases, plan to devote a substantial amount of time to working with your puppy across a range of needs.

- In the first few months, if you invested in socialization and training early on, you will gradually have fewer and fewer critical things you need to work on and your life with your puppy will become much easier, but you should still plan to devote a sufficient amount of time to fill gaps in socialization and work on training, including by taking at least one ‘Intro Obedience’ class.

Don’t worry, in the chapters that follow we will take you through each of the things you need to work on, why it is important, and how to go about it. For now, we just want to emphasize that you need to plan to put in a significant amount of time with your puppy, particularly in your first few weeks and months together.

Summarizing:

- Puppies don’t raise themselves! There are a slew of crucial experiences, skills, and behaviors you need to take them through. As we highlighted in the Introduction Chapter “Dogs Are Not Furniture” you have to teach your puppy, you are a parent, an educator to this dog. They do not magically become adorable, bonded, well-behaved adult dogs on their own!

- The first few weeks and months are crucial. You can’t ‘put it off’ til later. Plan to invest more time and energy in the first few weeks, or suffer more stress and time loss later.

That work will pay off: the time you put in now saves you more time and stress later, and sets your puppy up for success. Failing to learn what you need to do with puppies, and to make the time investment to do it, is a recipe for heartbreak, and jeopardizes your puppy’s future.

In the chapters that follow, we will take you through the most important things you need to do with your puppy in the first weeks, months, and years of your life together. Across them, you will need to get familiar with a puppy’s developmental stages, learn what and how to teach them and socialize them with in each of those stages, and put in the time (and patience) to help them grow into fun, happy, well-adjusted adult dogs.

Don’t worry: at first that may seem like a lot of work, and to an extent it is. You’ll see more concretely as we go, and we promise that process will be more fun and less difficult that it might look at first. And ultimately it is worth remembering: the work you put in now ultimately saves you time (and stress) later, we promise, on top of improving outcomes for your pup.

In the following chapters you will also see the potential consequences of not learning these concepts and putting in the effort. In total, if you don’t learn how to raise a puppy and put in the time to do it, you are creating a lifetime of problems, for you and your dog.

For example:

- If you don’t socialize your puppy, they may become aggressive to other dogs, people, reactive to loud noises, etc. – causing them and you stress, and posing a danger to others.

- If you don’t teach your puppy about appropriate ways to live in the home and give your puppy outlets for their high energy and curiosity, you may be limiting their coping skills and this stress may manifest in other ways.

- If you don’t gradually teach them to be comfortable spending appropriate amounts of time alone, it can get worse and worse, leaving them howling and barking nonstop – for hours – when you leave the house.

- If you don’t start teaching foundational behaviors, your puppy won’t develop the self-control, focus, and problem-solving skills that will make her and you happier and better partners throughout her life.

- And so on

What if I’m getting an adult dog? You should still be familiar with these concepts.

If you’re getting an adult dog, you should still familiarize yourself with the material in this section, for three reasons:

- All of the socialization concepts still apply

- Some of the most common behavioral issues that adult dogs suffer from are covered in this section (those behaviors come from their puppy experiences after all), along with how to address them

- Understanding how a dog’s experiences as a puppy translate into their adult personality, behaviors, and perception of the world around them will make it easier for you to see where your adult dog is coming from, empathize with them, and help them adjust to life with you

Chapter 1-1: Puppy developmental phases

Before we dive into specific best practices for owners in puppyhood, let’s take a look at the overall timeline of puppy development – the phases they go through, and what you can expect in each.

Getting familiar with puppy developmental phases

In the following Chapters in this Section – such as Socialization Basics, Fear Imprint Stages (fear periods), Chewtoy training, etc. – we will cover the range of critical elements of a dog’s puppyhood that set you and your puppy up for success.

Before we dive into those topics however, it is useful to step back and briefly survey, at a high level, what the various age-based stages of a puppy’s development look like.

Getting familiar with that timeline helps you:

- Understand what your puppy is experiencing at a given point in time, such as fear periods or rebelliousness, so that you can correctly interpret their behaviors – such as apparent regression from a week before – and respond to them appropriately, in a manner that avoids creating reactivity, damaging your relationship, or training bad behaviors.

- Know what you need to do for your puppy’s development, and when; such as ensuring that you socialize them sufficiently during their critical ‘socialization window’

- Provide a roadmap to organize the concepts we cover in other chapters

Other resources to consider

Once again, we want to emphasize that our treatment here is cursory, an introduction, meant to familiarize you with the basic concepts that you must – through both the remaining chapters in Section 1 as well as outside resources – go and learn. Notably, there are several wonderful books we can recommend that specifically go through the stages of puppy development:

- Ian Dunbar’s Before & After Getting Your Puppy

- Patricia McConnell & Brenda Scidmore’s The Puppy Primer

In addition, we will recommend a few books on specific topics throughout the Chapters that follow.

The Newborn Period (0-3 weeks)

Developmental milestones:

- Like human babies, puppies are born with highly limited brain, motor, and sensory functionality; initially they will rely on tactile instinct to suckle and nest with littermates

- Around the second and third weeks of life, they will start opening their eyes, motor functionality will gradually expand, and the first beginnings of exploration and curiosity will emerge

What your breeder should be working on:

- Provide the litter with appropriate spaces to nurse, sleep, potty and – eventually – explore and play. Chapter: Choosing a reputable breeder

- Begin early mild ‘stressors,’ such as touch desensitization, to start building resilience and adaptability that will help enormously in their first few months of life. Chapter: Choosing a reputable breeder

Socialization Period (3-12 weeks)

Developmental milestones:

- This is their critical ‘socialization window,’ a time period where they are more able to adapt to and grow comfortable with new experiences; after this window, exposing them to new stimuli – people, places, objects, animals – becomes considerably more difficult. Chapters: Socialization Basics, Socialization with & reactivity to strangers, Socialization with & reactivity to other dogs, Environmental Socialization

- First fear periods begin, between 7-11 weeks. Chapter: Fear Imprint Stages (fear periods)

- Although they’ll grow more active with each week, they will continue to nap most of the day (and should be allowed to! They need that nap time to continue physical and neurological development!).

- Bladder control will gradually improve, and careful potty training will help, but that even in the latter half of this window your puppy will likely need to potty at least once during the night, and every time they wake up from a nap during the day (every hour or so to start). See chapter for more details. Chapter: Potty training, penning, and the expanding circle of freedom

What you and your breeder should be working on:

Before go-home date (typically ~8 weeks), at your breeder:

- Human Socialization: Expand socialization with people (while following Socialization best practices! See Chapter Socialization Basics), appropriately introducing the puppies to as many people as possible.

- Environmental Socialization: Start environmental socialization, introducing the puppies to a variety of new places and objects (while following Socialization best practices! See Chapter Socialization Basics). Chapter: Environmental Socialization

- Vet visits & vaccines: Take to vet for first medical examination and vaccinations. Chapter: Medical schedule, vaccines, and vet visits

- Personality Test: Bring in a trainer to conduct an aptitude/personality test. Chapter: Puppy personality variation

- Home Placement: Place puppies, deciding on what the most appropriate puppy for each home is. Chapters: Choosing a reputable breeder, Lifestyle fit of dog breed & personality

- Crate training: Ideally, although it is rarely done, start introducing crates and early crate-training. Chapter: Crate training

After typical go-home date (~8 weeks):

- Human Socialization: Continue (or start, if your breeder hasn’t) human-socialization, introducing your puppy to 200 people in their first 12 weeks of life (4 weeks after you get them)! Chapters: Socialization Basics, Socialization with & reactivity to strangers

- Environmental Socialization: Greatly expand environmental socialization, introducing your puppy to every kind place, sound, object, and stimulus that you could conceivably want them to be comfortable with at any point in their life. Chapters: Socialization Basics, Environmental Socialization

- Dog Socialization: Begin introducing your puppy to other dogs, in: carefully controlled scenarios; with dogs that are not reactive, do not resource guard, have low ‘aggression responses,’ are well-socialized, and are fully up-to-date on their vaccines; and with you present and carefully monitoring the interaction. This socialization helps teach your puppy how to accurately read and project dog body language, and avoids developing reactivity later. Chapter: Socialization with & reactivity to other dogs

- Play & Problem-Solving: Play with your puppy! Give them plenty of time to nap, but also start investing in play. Also start creating age-appropriate ‘challenges’ for your puppy, giving her problems to solve to develop her confidence, self-control, perseverance, curiosity, and intelligence. Chapter: Playing with your puppy & teaching her problem-solving

- Early manners Training: Begin early ‘training’ as part of play, to build foundational skills, build your relationship, and start good habits. Chapter: Behavioral training the first year

- Crate Training: Crate-train your puppy. Chapter: Crate training

- Chewtoy Training: Chewtoy-train your puppy. Chapter: Chewtoy training

- Bite Inhibition Training: Start bite-inhibition training. Chapter: Bite inhibition

- Potty Training: Start potty-training. Chapter: Potty training, penning, and the expanding circle of freedom

- Expanding Circle of Freedom: To teach good behaviors in an ‘errorless’ fashion (which we’ll explore in-depth), you will initially limit the space in which your puppy has unfettered freedom, gradually expanding that circle as you start to reinforce appropriate behaviors – like not pottying indoors, and not chewing on non-toy objects. Chapters: Potty training, penning, and the expanding circle of freedom, Errorless learning

- Separation Anxiety Prevention Training: You will very slowly and very carefully begin separation anxiety training. Chapter: Separation anxiety

- Grooming Exposure: Begin grooming ‘training’; they don’t need a lot of husbandry to start, but now is the time to start getting them comfortable (and happy!) to have their ears, paws, mouth, etc. handled. Chapter: Cooperative care

- Vet visits & vaccines: Continue appropriate medical examination and vaccination schedules. Chapter: Medical schedule, vaccines, and vet visits

Aside: Your first 4 weeks together are busy and critical – but pay off! Don’t be scared!

There are a couple things worth pointing out in the 3-12 week developmental phase:

- The socialization window is short! If you take your puppy home at 8 weeks, you only have 4 weeks to lay strong socialization foundations. As we will talk about in Chapter 1-2: Socialization Basics you absolutely can make up for lost time later, but any socialization you do after this 3-12 week window will have to be slower and more careful.

- There is a lot to do in these first few weeks! The list above might rightfully seem daunting. While getting used to a new puppy, you also have to work on potty training, crate training, separation anxiety training, grooming exposure, etc. etc.

You might look at all that and be terrified, thinking “I can never do this!” DON’T PANIC! It’s not as bad as it looks! As we mentioned in Aside #3, there’s a few things that are going to help you:

- The first 4 weeks are busy, but it gets easier from there – not only do you get in the swing of things, but there is just less and less you have to work on as your puppy matures. As we will discuss in Section 3: A Dog’s Basic Needs, you will have to provide your dog with physical activity, mental stimulation, work/training, and your own company throughout their lives; but the extent of those needs peaks in these first months and tapers down fairly quickly over time.

- The more you do now, the less you have to do later – the reason we encourage you to do so much in the first 4 weeks you have your puppy is that these are all easier to do if you do them now. Not only are you in the core socialization window, but as we will cover in Errorless learning, bad habits are a lot easier to avoid than they are to un-train. If you put in the work early on, you save yourself a lot more work and stress later on!

So don’t be intimidated – you will be fine! The important things – and what we are really trying to get across by taking you through that checklist above – are:

- Prepare before getting your puppy: familiarize yourself, through this primer and other resources, with the things you need to teach your puppy before getting your puppy. Waiting until after you get your puppy to start studying will just increase your stress and workload.

- Budget extra time in the first 2-4 weeks: planning and allocating enough time in that first 4 weeks will save you so much time later on. Try to arrange a lighter work schedule for the first 2-3 weeks you have your puppy, and clear off any other non-essential responsibilities in that time. Give yourself the space you need! Again, it will pay off down the road

Pre-Adolescent Period (12-24 weeks)

Developmental milestones:

- In this period, your puppy will increasingly sleep less, and start being more active. They’ll want (and need) more physical activity and mental stimulation. Chapters: Section 3: A Dog’s Basic Needs

- While the core ‘socialization window’ will be closed, they will still be more open to socialization than later in life, and you should continue to do so.

- Fear periods may recur periodically, depending on the dog. Chapter: Fear Imprint Stages (fear periods)

What you should be working on:

- Ongoing Socialization: You should have achieved most of your socialization goals by this point already (see above). However, (a) deliberate, appropriately-executed socialization should continue throughout their first two years of life, and (b) there will inevitably be gaps in their socialization, which you should work on carefully filling. Chapters: Socialization Basics, Socialization with & reactivity to strangers, Socialization with & reactivity to other dogs, Environmental Socialization

- Physical Activity & Open-Ended Exploration: You should start providing your dog with more and more opportunities for physical exertion and open-ended exploration, such as long-line hikes, sniff-aris, and play sessions with other (appropriately-chosen, see above) puppies and dogs. Bear in mind age-appropriate limits however. You cannot rely on puppies to self-regulate, and over-exertion at this age can lead to joint and muscle problems later in life. Chapters: Puppy exercise and over-exertion, Need for physical activity, Need for open-ended exploration

- Manners Training: As they start to mature and their self-control and mental faculties expand, continue with associative learning, both informally during play sessions/life interactions and formally in short training sessions. You will start with simple and foundational behaviors such as Sit, Down, Give, Touch, and Leave It, and eventually work up to more advanced behaviors and ‘tricks.’ Chapter: Behavioral training the first year

- Expanding Circle of Freedom: As your puppy matures and continues to be prevented from engaging in ‘bad’ behaviors (like stealing food and chewing on furniture), you will continue to gradually expand the space in which they have unfettered access. Chapter: Potty training, penning, and the expanding circle of freedom

- Separation Anxiety Prevention Training: You will continue separation anxiety training. Chapter: Separation anxiety

- Grooming: Continue grooming exposure to build adult grooming habits. Chapters: Section 5: Husbandry

- Vet visits & vaccines: Continue appropriate medical examination and vaccination schedules. Chapter: Medical schedule, vaccines, and vet visits

Adolescent Period (6-18 months)

What you should be working on:

- Ongoing Socialization: You should have achieved most of your socialization goals by this point already (see above). However, (a) deliberate, appropriately-executed socialization should continue throughout their first two years of life, and (b) there will inevitably be gaps in their socialization, which you should work on carefully filling. Chapters: Socialization Basics, Socialization with & reactivity to strangers, Socialization with & reactivity to other dogs, Environmental Socialization